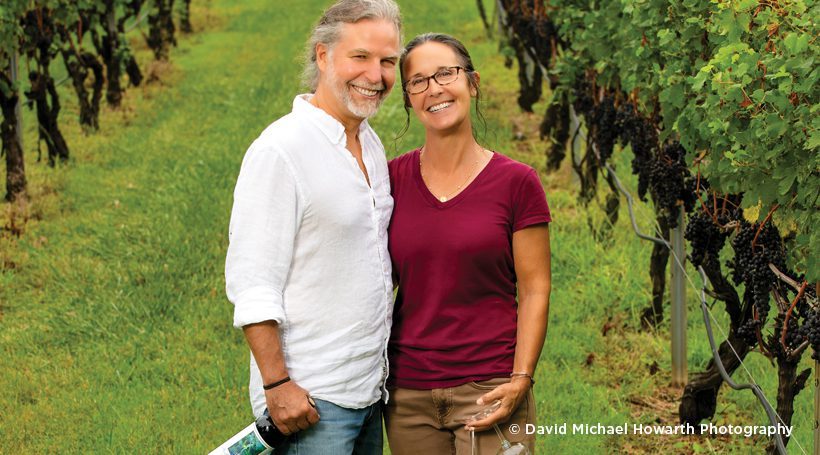

When Scott and Jules Donnini swapped city life for greener pastures in Salem County 20 years ago, their dream of opening an Italian-style wine bar raised more than a few eyebrows.“We wanted Auburn Road to be a place where you would want to bring your family – kids, grandma, the dog,” says Scott, about the vineyard the couple owns and manages in Pilesgrove. “We envisioned having live music, pizza, gelato, cappuccino and of course wine.”

Scott & Jules Donnini appeared in SJ Mag in 2013. They had just opened Auburn Road.

Given the novelty of their vision, they faced some challenges. “The township had nothing to compare us to – so much so that when we went to the planning board, they thought we were crazy. Of course we were Philadelphia attorneys, had never farmed a day in our lives or even made a drinkable bottle of wine. And here we show up, telling them ‘we’re going to make alcohol, invite your kids and grandparents to hang out.’ Nobody knew if this was going to be a free-for-all drunk fest or what.”

Two decades later, the answer is clear. With its rustic tasting room and courtyard surrounded by rolling vine-covered hills, Auburn Road may best be described as a destination.

Visitors flock to Salem from as far south as Washington, D.C. and as north as New York, savoring wine, live bands and wood-fired pizzas. While their well-rated wines find buyers across state lines, the bulk of the 7,500 bottles sold annually is purchased inside the vineyard.

Auburn Road, along with dozens of other growers working to elevate New Jersey’s wine-making status, offers more than just exceptional wines. Their true ambition extends beyond the wine bottle: they’re crafting an experience that aims to stand alongside renowned wine destinations like Tuscany and Bordeaux – regions steeped in centuries of wine lure and culture.

“Collectively, really what we are selling is the agritourism experience, because wine and tourism are inextricably intertwined,” Scott says.

Growth in grape ventures

While much progress has been made to promote agritourism in New Jersey, Scott and his fellow growers know they are underdogs in the worldwide industry.

“At this stage in the game, the reason you may pick, say, a chardonnay from Auburn Road over a more established French one is because you’ve been to our vineyard,” Scott says. “Maybe you’ve tasted the grapes off our vines and talked to the winemaker. These are the types of experiences people go to France, Italy or California for, but what we offer is a lot closer to home.”

In 2004, when the couple planted their first grapes, only 26 vineyards were licensed in New Jersey. Today, that number has soared to over 60. Statewide, the industry is the toast of the town, says Devon Perry, executive director of the Garden State Wine Growers Association, headquartered in Haddonfield. Wine destinations last year attracted over 272,500 enthusiasts, boosting the local economy by around $4.5 million, she says.

“Our wines hold the exclusive honor of being poured at Drumthwacket, the governor’s residence,” says Perry. “Top restaurants across the state pair dishes to our wines, and we’re collaborating on tasting events with culinary leaders, including Jose Garces and restaurant groups in Atlantic City.”

Moreover, she says, upscale restaurants are increasingly showcasing local vintages. Notably, this includes Cherry Hill’s Caffe Aldo Lamberti, celebrated multiple times with Wine Spectator magazine’s seal of excellence for its carefully curated selection.

Michael Snyder, with Visit South Jersey, a state-funded tourism promotion group that partners with the Wine Growers Association, has also observed New Jersey wines’ success.

“Years ago when I mentioned our state’s vineyards, few knew they existed,” says Snyder. “Now when the topic comes up with the same people, they’re the ones sharing stories of their amazing experiences on our wine trails and how they can’t wait to come back.”

“Due to the quality of wines, the vineyard experience and our collective efforts to speak with one voice, the message is getting out there,” he adds. “While the wineries are just one of the great assets that bring people to the region, it just adds to a complete visitor experience.”

But New Jersey wines aren’t only making waves in the U.S – there’s international intrigue as well. So much so that it’s now possible to imagine a future where bottles of chardonnay or merlot from New Jersey could grace the shelves in places like Mantua and Verona – not the New Jersey towns, but their Italian namesakes.

Highlighting this growing global interest, the Garden State Wine Growers recently hosted 2 Italian sommeliers. Their mission was to explore bringing lesser-known boutique American wines to Italian markets. The 3-day tour in June included 11 vineyards crisscrossing the state. It culminated in a blind wine tasting event at Tomasello Winery in Hammonton.

As Perry describes it, it was a whirlwind occasion, bringing together winemakers, journalists, politicians, educators and influencers – all focused on experiencing and celebrating N.J. wines.

“Our wines have been winning competitions for decades,” says Perry, “But now we have a bigger megaphone and opportunity to share them with the international wine community and gain the respect our wines have deserved for decades.”

Birth of a fine-wine industry

New Jersey’s late bloomer status is seeded in both Prohibition restrictions and the soil itself. Although grapes have been grown and wine made here since colonial days, the industry was nearly brought to its knees during the 1920s. Apart from a few wineries, including Renault in Egg Harbor City (which was permitted to continue producing for church or medicinal purposes) many vineyards shut down during the 13 long years when alcohol was outlawed.

Even 5 decades after Prohibition, its effects were still felt. New Jersey’s rigid licensing allowed only one winery license per million residents, reducing the industry to just 7 statewide by the early 1980s. Hard-fought reforms – including a law allowing N.J. farms with 3 or more acres of grapes to produce and sell wine – spurred growth.

But that didn’t solve all the issues facing growers. Up until the 1970s, the only wine that flourished on the East Coast was created solely by using sweeter grapes native to the lands. Although the weather in South Jersey is similar to the great wine regions in France, pests native to the East Coast were a barrier to growing the sought-after dryer varieties here, says Louis Caracciolo, founder of Amalthea Cellars in Atco.

“Even Thomas Jefferson tried to plant the grape that produces the European greats here only to have them all die from black rot,” he says.

Fortunately for Caracciolo, by the time he purchased his farm in 1972, breakthroughs in agriculture had paved the way for growing old-world grapes in South Jersey.

But winemakers faced another major hurdle: State law still prohibited them from shipping their product out of state. When those restrictions finally eased, it paved the way for the modern industry.

Over the decades, winemaking here evolved organically, notes Perry, with new entrants like the Donnini’s moving to winemaking as a second career and others transitioning traditional farms to vineyards. Among these were 5th generation farmers Bill and Penni Heritage, who converted their family’s peach and apple orchards to vineyards in 1999.

Still, until 2012, N.J. wines largely went unnoticed despite the growth in wineries and improvement in vintners’ skills. The narrative shifted when international wine connoisseurs convened in Princeton to compare New Jersey wines to esteemed French Bordeaux and Burgundy wines in a blind taste test. Dubbed “The Judgment of Princeton,” it is celebrated as a landmark event, says Perry, noting that it proved New Jersey’s best wines could stand shoulder-to-shoulder with those from world-famous wine regions.

And from that moment on, she says, wine distributors, influencers and wine lovers alike were forced to take N.J. wines more seriously. “It took going head-to-head with wines well-known within the international wine community for New Jersey winemakers to get the respect they had deserved for decades,” says Perry.

Since that defining moment, New Jersey’s industry has seen consistent growth. Wine tastings happen year-round while some of the larger vineyards are the scene of popular music festivals – Rootstock at Hawk Haven Vineyard & Winery sold out for 8 weeks straight this past summer while the Valenzano Winery’s WineFest has grown to a 2-day event that includes 3 stages of live entertainment, food trucks and dozens of wines to taste from 13 local vineyards.

Meanwhile, the state’s official grape-growing regions, known as viticultural areas, are easier to navigate thanks to the Garden State Wine Grower’s mobile app. It offers self-guided tours with trails that cluster wineries located within a short drive of each other. For example, the Two Bridges Wine Trail covers wineries between the Delaware Memorial and Commodore Barry Bridges, spotlighting 10 wineries, including Auburn Road and Heritage.

Interest in winegrowing has also spurred Women in Wine, a subgroup of the Wine Grower Association that is partnering with organizations that support women, including the Alice Paul Institute.

“It gives us a unique way to tell the story of the wine industry,” says Perry, noting that some might find it surprising how many women are the ones in charge of running their vineyards, including Jules Donnini at Auburn Road.

Camden County planted a vineyard 3 years ago at its Sustainability Campus in Blackwood

Meeting grape expectations

The increased demand for New Jersey wines has brought fresh challenges, primarily the escalating need for more wine-worthy grapes. In response to this, Camden County stepped in to help 3 years ago. The goal of planting 1,100 pounds of grapes on its Lakeland campus was to supply local wineries and create more jobs. In 2022, the campus’ chambourcin harvest saw a staggering 400% yield increase compared to 2021 and this year promises another outstanding yield, says Camden County’s Dan Keashen.

“It’s early, but we can say definitively that the crop continues to grow year by year and we get better at protecting the vines from the elements and the wildlife,” Keashen says. “We will be looking to work with our local wineries to create another partnership to make some of the best outer coastal plain wines in the state.”

The forthcoming Saddlehill Cellars in Voorhees also shows a new pathway for winemaking. The land, once a gift from then-Continental Army General George Washington to his personal guard John Stafford, narrowly escaped becoming a housing development in the early 2000s when government entities and a non-profit organization pooled together $20.6 million for its acquisition. Entrepreneur Bill Green purchased the land in 2021 and is expected to open the location as a blend of winery, horse stables and a floral/produce stand this spring.

Perry views the Saddlehill initiative as a blueprint for other endangered farms and historic properties. As Scott Donnini sees it, not only is there room for more players, winemaking in New Jersey is like making a go of frontier life in the Wild West.

“We’ve been putting grapes in the ground, pulling things out and moving them around on our property for the last 20 years trying to find the right place to put the right vines. And truthfully, that’s what the whole industry is doing,” he says. “We’re all still trying to learn how to get the most out of soil, our climate, everything. It’s what’s so exciting about being such a young wine region.”