Photography David Michael Howarth (unless otherwise noted)

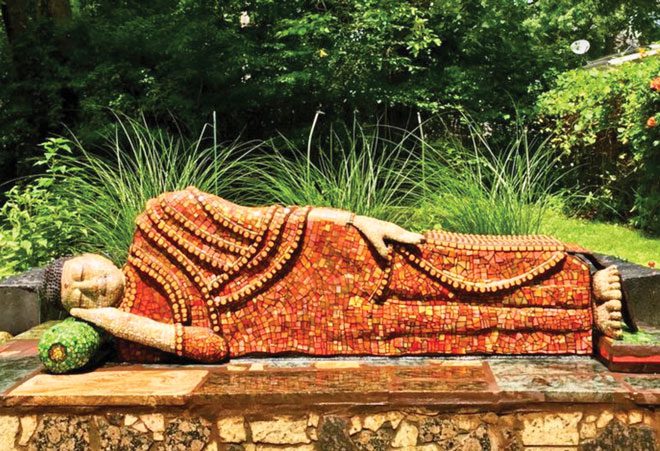

Photo courtesy Perkins Center for the Arts

If you wander the backroads of South Jersey, you’ll find a landscape that often reveals unexpectedtreasures: towering robots crafted from scrap, birdhouses worthy of fairy tales and castles spun from glass and stone. These artscapes transform the familiar into the fantastical, turning everyday materials into stunning, imaginative works. It’s a world where art breaks free from galleries, and each creation tells the story of passionate hands and minds at work.

77-year-old Sally Willowbee – whose given name is actually Willoughby – has spent the past two decades documenting the phenomenon of what she has named artscapes.

“It’s outsider art, which is different from outdoor art,” she explains. “This art is made by people with no formal training. Often, they come to art by accident, sometimes after an injury or maybe when they retire and suddenly have the time. They find a side of themselves they didn’t know was there when they were younger and busy working and raising families. I think everyone has a creative side, some of us just find it later in life.”

That is one of the challenges of outsider art. There has to be someone who wants to continue its legacy.”

Willowbee is an artist, writer and activist. She’s also the author of “Found Artists: On the Country Roads, Side Streets and Back Alleys of South Jersey” and a founding member of the Philadelphia Dumpster Divers, a group passionate about keeping discarded items out of the trash and repurposing them creatively. She found an instant fascination with outsider art.

“My first experience was in the 1970s,” she recalls. “That’s when I visited Grandma Prisbey’s Bottle Village in Simi Valley, California. It was unlike anything I had ever seen before. Here was an old woman who, after she retired, started building these monumental bottle buildings, shrines, wishing wells and mosaic walkways with throwaways from the local dump. The structures were made from tens of thousands of discarded bottles. Nobody lived in these buildings, but they were filled with her creations. I remember a pencil room with items made from pencils she’d collected. It was my first time seeing art like this, and it really inspired me.”

“My first experience was in the 1970s,” she recalls. “That’s when I visited Grandma Prisbey’s Bottle Village in Simi Valley, California. It was unlike anything I had ever seen before. Here was an old woman who, after she retired, started building these monumental bottle buildings, shrines, wishing wells and mosaic walkways with throwaways from the local dump. The structures were made from tens of thousands of discarded bottles. Nobody lived in these buildings, but they were filled with her creations. I remember a pencil room with items made from pencils she’d collected. It was my first time seeing art like this, and it really inspired me.”

That led Willowbee to seek out similar sites during her travels, and she found them everywhere – in northern America and in Europe.

“I started photographing them, then documenting them and engaging with the people who created them, even in countries where I didn’t speak the language,” she says. “These were ordinary people creating extraordinary art with their own two hands. I started reading everything I could find about self-taught art, about yard art, vernacular art and the meanings embedded in these unique visual expressions.”

She looked for this unique art closer to home when she returned to South Jersey. Among the hidden artscapes she discovered was a living topiary garden in Lower Township created by Gus Yearicks.

Photo courtesy Perkins Center for the Arts

“I think of a topiary garden as something very formal, but this was not your ordinary garden,” she says. “It was incredible – an entire landscape sculpted into scenes from American history from a clipper ship to the Liberty Bell and the Statue of Liberty. It even had America’s pastime, baseball, featuring an entire team in mid-play. When I visited, Gus was in his 90s and still growing new ones.” Yearicks passed away in 1986, and his son honored his request to destroy his creations rather than have them become overgrown.

“That is one of the challenges of outsider art,” notes Willowbee. “There has to be someone who wants to continue its legacy.”

Willowbee started her own outsider art installations at her family’s farm in Deptford, a 300-year-old property known as Old Pine Farm. Willowbee is now sole caretaker and resident artist. “I’ve been decorating the property with metal flowers on the shed,” she says. “I call them my gardens. There’s a garden of black-eyed saws and a Garden of Good Trouble in honor of my parents. Art is expression, and for me, it’s a tribute to the things that matter most.”

An appreciation for art runs in her family, and her brother Alan Willoughby served as executive director for the Perkins Center for the Arts for 25 years. About the time that he retired in 2016, the Perkins Folklife Center was created, in partnership with the New Jersey State Council on the Arts (NJSCA). Outsider art falls within the umbrella of folk art, and Willowbee found a kindred spirit in Perkins Folklife Center Director Marion Jacobson.

“These are passion projects, usually created in large scale,” says Jacobson. “Sally and I worked together to come up with the term artscapes to describe them. Whether working in recycled or discarded materials from their occupations and everyday lives, these individuals capture the time, place and spirit of their region.”

“There is always a story behind the art,” notes Willowbee, “something that I’ve learned as I’ve talked to the artists.” She shared some artscapes from a recent tour that she helped curate for Perkins. (Perkins hosts an Artscapes tour a few times throughout the year.)

“Dan Dennison actually grew up very near to where I live,” she says. “He worked at the New Sharon Iron Works in Deptford and later ended up buying it. Then the economy tanked, and in 2009, he closed the business. That’s when he started to make art. He used the same materials that he used to make signs and gates.”

Now two large sculptures are on his front lawn, nicknamed The Condo and The Apartments. His backyard includes more whimsical pieces such as painted metal springs that sprout among the living plants and a tree decorated with blue washers. He sometimes holds open houses at his property.

The Arbuckel Liberty House in Vineland is home to New Jersey’s “other” Statue of Liberty. Built by engineer George W. Arbuckel, who bought the house in 1919, the entire structure is coated in cement mixed with mica and black coal, making it sparkle in the sunlight. A 30-foot Lady Liberty stands atop a gazebo surrounded by sculpted archways and statuaries.

Photo courtesy Perkins Center for the Arts

In Egg Harbor City, Peterson’s Service Center offers a metallic Statue of Liberty with sparkplug fingers and other parts salvaged from old cars. She’s one of many “scraptures,” as creator Tom Peterson calls them. Since 1991, he’s transformed old car parts into life-sized figures, including muffler men, a dinosaur, a knight and even a working guitar.

The Palace of Depression in Vineland is a site rich in history and intrigue. “The Palace of Depression was famous in the 1930s,” says Willowbee. “George Daynor built this spiral dome house during the Great Depression, using local materials and trash. He charged visitors 25 cents to explore, and it became an important piece of Vineland’s history.”

“Legend has it,” Jacobson adds, “that Daynor lived off frogs and squirrels he hunted nearby. A bit of a publicity seeker, he falsely confessed to a kidnapping case and went to federal prison. When he got out, he found his palace vandalized by locals who didn’t appreciate the scandal he’d brought to the area.”

After Daynor’s death, Vineland residents Kevin Kirchner and Jeffrey Tirante rebuilt the Palace with the help of 400 volunteers. “Kirchner grew up playing in the palace as a child,” says Willowbee. “As the building inspector, he directed the restoration, rebuilding according to code but using recycled materials wherever possible. It’s spectacular, just spectacular.”

Since many of these artscapes are on private property, Willowbee advises checking first to see if visitors are welcome. Perkins offers a guide to outsider art, and some artists share updates on their Facebook pages. Others welcome visitors by appointment. Some also sell their work.

“There are so many reasons to celebrate outsider art,” says Jacobson. “It’s essential to recognize the cultural assets of our communities, or we risk becoming a country of shopping malls and chain stores. Artscapes make places like South Jersey unique. This region is underserved when it comes to art and culture, and recognizing these artists helps connect them with exhibits and networking.”

“We’re losing our landmarks,” adds Willowbee. “You could be anywhere when you see a McDonald’s and a Target. But you know exactly where you are when you pass the hubcap pyramid in Mays Landing. You’re on the way to the Shore.”

“Next time you see a piece of outdoor art, stop and appreciate it,” she encourages. “If you feel comfortable, knock on the door. Many artists are happy to chat. Take photos, tell friends, and seek out these hidden pieces. Art lives around every corner and in unexpected places, waiting to be discovered.”