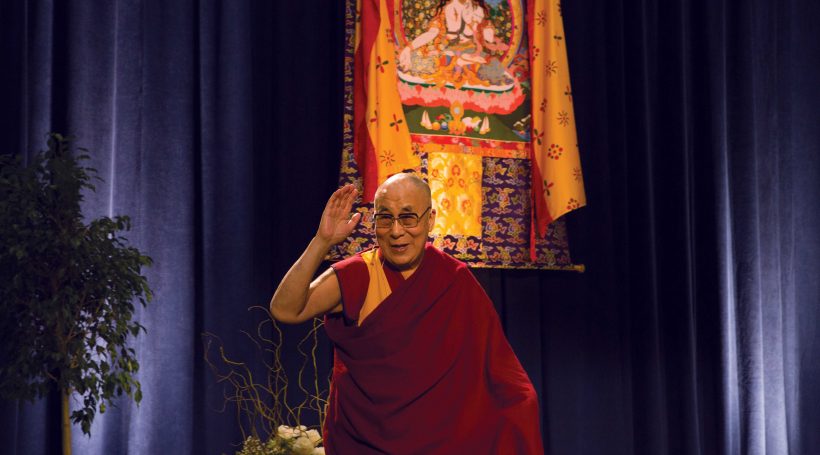

The Dalai Lama greets students and guests

The Dalai Lama may not be a great orator, but he is a truly powerful speaker. The diminutive spiritual leader of Tibet speaks softly and deliberately, carefully choosing each word. And while you might think his drawn-out pauses would encourage whispers or rustling in an audience, there is none. At a recent lecture to more than 4,200 people at Princeton University, the crowd sat, silent and spellbound.

The Dalai Lama was welcomed and introduced by Rev. Dr. Alison Boden, Princeton’s dean of religious life and the chapel, who gifted the bald Buddhist monk a bright-orange Princeton University baseball hat, which he immediately donned.

With occasional help from translator Thupten Jinpa, His Holiness spoke about compassion in a talk titled “Develop the Heart.” He began with a discussion about how the responsibility individuals have to one another has changed in modern society. He spoke with broken English, but his message was clear.

“I listen to news. I always listen BBC, not American CNN,” the Dalai Lama joked. “But when I listen, I think in one way world has had much development, life much easier with help technology, with help science. It’s wonderful. But same time, lot of man-made problem. I think firstly, huge gap between rich and poor, everywhere, including America. Then corruption. Some countries really have a lot of problems.”

His Holiness said the advent of technology has been positive in many ways, but also increases the distance people feel from one another.

“Great achievements, through technology and science, sometime help create more fear, more destruction,” he said. “Basically, we are social animals. Each individual’s future depend on rest of community. And today, because of global economy and problems with environment, now we cannot say, ‘This place safe, this other place not, but that other place not your concern.’ No, the reality is East depend on West, West depend on East. South depend on North. We need a sense of global responsibility, because well-being of humanity is your own well-being.”

The Dalai Lama said he was honored to have an opportunity to, he hopes, inspire people who are uneducated about Buddhist Tibet’s customs and traditions, and to teach them its rich history.

The Dalai Lama is the head monk of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, a sect that controlled the Tibetan government for several periods between the 17th and 20th centuries. The first Dalai Lama came to power in 1357, and when a Dalai Lama dies, the high monks of the Gelugpa tradition and members of the Tibetan government set out to find his reincarnated successor.

The 14th Dalai Lama, whose religious name is Tenzin Gyatso, was selected as the reborn Dalai Lama in 1937, at the age of 2. He was born to a family of farmers, and has pleasant memories of his mother. He told the Princeton crowd she was “uneducated, but very kind,” and the first to teach him compassion; he remembers riding on her shoulders and moving her ears to make her change direction. “I was a young, spoiled boy,” he laughed.

Gyatso was formally recognized as the Dalai Lama at 15 in 1950, during an invasion by The People’s Liberation Army, a communist Chinese military force. The Chinese government has long claimed sovereignty over Tibet, much to the discontent of many Tibetans. In 1951, a Tibetan delegation representing the Dalai Lama signed an agreement establishing China’s sovereignty but preserving Tibet’s national autonomy. In the decades since, it has remained unclear whether the Tibetans signed the agreement under duress.

By 1959, conditions in Tibet had deteriorated under Chinese rule, and a national uprising swelled with the support of the American CIA. Within three days, between 10,000 and 15,000 Tibetans were killed, and the Dalai Lama, with the CIA’s assistance, fled to India, where he established a Tibetan government, called the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), in exile.

Present-day Tibet is administered by the People’s Republic of China, a situation the Dalai Lama and the CTA regard as a military occupation. China, however, argues that the Chinese government has held sovereignty over Tibet for 700 years, and it has never been an independent nation. In speeches before the United Nations, the Dalai Lama has said if independence is impossible, he would accept Tibet as a genuinely autonomous region within the People’s Republic of China.

Interpreter Thupten Jinpa, the Dalai Lama and Rev. Dr. Alison Boden on stage at Princeton University

On the lawn outside the lecture hall in Princeton, several hundred Tibetans and Americans with Tibetan ancestry performed traditional songs and dances to welcome the Dalai Lama. Tashi Sharjang, 57, a Tibetan man who lives in Howell, N.J., said he hoped the Dalai Lama’s visit would put a spotlight on Tibet’s ongoing political plight.

“I came here in 1992 when the United States passed a resolution to allow a thousand Tibetans to come to USA,” Sharjang said. “I’m happy to see His Holiness here. He is an embodiment of compassion, peace and love to the world, and he represents the issue of Tibet to the world. Whenever he visits, he is the voice of six million Tibetans, and those issues come to the forefront.”

Sharjang traveled to Princeton in a convoy of 11 buses from the New York City area. He said he and the other passengers chose not to purchase tickets to hear the Dalai Lama’s talk because they wanted to demonstrate Tibetan traditions to the greater community. Many of those dancing wore brightly colored, traditional Tibetan clothing, and the dances, Sharjang said, were significant in Tibetan culture.

“We didn’t want to go in because we want the whole community to enjoy, and warm their hearts and open their minds, and show the world something about world peace, religious harmony and the issue of Tibet,” Sharjang said.

Tenzin Yangzom came to Princeton from her New York City home because she thinks it is important to stay connected to her Tibetan roots.

“I was raised in India and I came to America in 2005, but I am Tibetan,” Yangzom said. “The issue is a country of people who have lost our home. We lost a whole race, a whole country. We want people to understand this feeling, no matter what race or nationality you are. Tibetan is a peaceful race; instead of violence we use positivity, like here, now, we are using song and dance to tell our story.”

Just a few dozen feet away, another crowd was gathered. While the atmosphere was no less celebratory, the signs and singsong chants of “false Dalai Lama, give religious freedom,” made it clear this was a protest.

Members and supporters of the International Shugden Community, another sect of Buddhism, had gathered with signs, banners and musical instruments to protest religious persecution they face in Tibet and India.

“We’re protesting against a campaign of discrimination and ostracization that’s been directed toward a faith community,” said Nicholas Pitts, spokesman for the International Shugden Community. “We’ve never been granted an audience with the Dalai Lama, so we’re forced to engage in demonstration.”

Press and educational materials being distributed by the group included photos of signs on public buildings forbidding service or entrance to those who practice Shugden Buddhism or, in some cases, those who fraternize with its practitioners.

“The way the discrimination has manifested is shops, restaurants, even medical clinics refusing service to people of this faith or even people who associate with people of this faith,” Pitts said. “They’ve been made into outcasts. A lot of these people are living in India, because they’ve left Tibet to try to escape the discrimination.”

The large crowd of protestors included people from all over the world working to end discrimination on the basis of religious beliefs. Pitts explained that the group would be happy to see the Dalai Lama remain in power; they simply want him to repeal the ordinances that single out Shugden Buddhists and take down the discriminatory signage.

Outside, some sang in protest and others danced in celebration. Inside, the Dalai Lama spoke about overcoming differences to establish love and respect between peoples.

His Holiness counseled that if each individual could find compassion in their heart for their fellow man, peace would follow.

“We need genuine cooperation and a sense of care for each other,” he said. “We need sense of oneness with humanity. Where I go, I see, whether believers or non-believers, we all want a happy life. We don’t want suffering. So live a meaningful life. Meaningful mean peaceful, mean living your life with compassion. If you live your life with a sense of well-being of others – no possibility harm others, exploit others, bully others, cheat others.”

“Yes, we have differences,” he said. “Different professions, different family, education, also color, also faith. If we more emphasis on sameness, no basis of quarrel.”