Photo: David Michael Howarth

The legacy of Mayor Vic Carstarphen will be simply told: Moments of his life have all led to him shaping Camden into a thriving city. He became accustomed to championships as a star basketball player at the city’s high school. And he took that mentality with him to city hall, where today, Carstarphen and most importantly, the city and its residents, are winning.

The way Vic Carstarphen describes his last time coaching the Camden High School Panthers is feeling the energy of the night fizzle as an all-but-assured victory dribbled away. It also helps explain why one of Camden’s legendary basketball players is now the city’s mayor.

There was an air of destiny surrounding Carstarphen and his Panthers heading into the 2019 South Jersey basketball cham-pionship game. Although it was his first year as head coach, few doubted that this former player – who had led Camden High to 2 state championships in the late 1980s – could take this team to such heights. But first things first. The Panthers had to get past their local rivals, Haddonfield High School, and the Bulldawgs weren’t going to make that easy.

“We were winning at halftime, up 16 or 17 points,” he says. “We wound up losing that game in overtime in one of the most intense games you can imagine. I felt like I let the city down.”

Days later, Carstarphen quit coaching, announcing a run for city council. Just 6 months later he was appointed as Camden’s interim mayor, a position he won in an election landslide in 2021. While the basketball loss will always sting, he now looks at the defeat as a win in disguise.

“If we had won, I would still be coaching. I’d be all in on coaching,” he says. “I didn’t understand at the time there was another direction where I could help the city even more.”

Carstarphen is all in – just working on a different court. He is leading a city that is, by all measures, on the rise. Unemployment is low and crime is down to levels not seen for more than half a century. Schools are producing significantly more college-ready graduates as new construction is reaching all corners of the city. The bustling Hilton Garden Inn – the first new hotel to come to the waterfront in at least half a century – coupled with Cooper 11 – the first market- rate apartments to hit the market in 20 years – are signs that some $3 billion of private and public money pumped into the city in the past decade has been a good investment.

Another indication of better times: The city’s bond rating, which was in junk range for years before the turnaround, was boosted last year to an “A-” by Standard & Poor’s. That’s making it easier and cheaper for the city to borrow money to fund capital projects – including $35 million in federal funds to replace Ablett Village, the city’s oldest housing project, in Cramer Hill – and to attract new investors.

Camden Mayor Vic Carstarphen outside his childhood home in Camden. “This is where I come from. This is a part of me.” Photo: David Michael Howarth

If his rise in city government seems to have had the momentum of a breakaway, Carstarphen, a point guard in his playing days, says all that he learned as an elite player and coach really does apply to being mayor. Most valu-able of all, he says, is the wisdom of knowing how much he depends on his team to win. By team he means everyone and any-one invested in Camden – from city residents and municipal workers to the CEOs of major industries now headquartered at the waterfront and their employees.

But it’s bigger than that. For Camden to be great, people who live and work in surrounding towns need to be invested too, he says, because “when Camden is in a good space, South Jersey is in a good space.”

His definition of winning, he says, is tied to building on the momentum of the recent past to bring Camden to even greater heights. As the city’s mayor, his primary role is to unite all those players, encouraging team-work and collaboration.

“Camden winning is what I want, not my name in the spotlight,” Carstarphen says. “I’m fortunate that I get a chance as mayor to wake up every day with the distinction of being able to make change happen. But it’s not me. I always say it’s a ‘we thing. It ain’t a me thing.’ You can’t have an ego in making Camden great. As I learned from coaching, if we’ve got differences, we have to figure them out.”

He likes giving credit where it’s due, particularly to the people who in the recent past made hard choices. Those choices, he notes, delivered Camden out of the mire of being named the most dangerous city in America for several years. Among them, he singles out former Mayor Dana Redd for dissolving the Camden City police department more than a decade ago. That paved the way for the establishment of the Camden County

Police Department that has been a pioneer of community policing.

And while Carstarphen doesn’t want the spotlight, he does want to be seen by his community as much as possible. He’s often out on the streets, seemingly in several places at the same time – sometimes flanked by a high school cheer squad and usually amplifying his voice with the help of a bullhorn.

The approach proved effective 2 years ago when the city was trying to boost its Covid vaccination rate from 50 percent to at least 70 percent. Carstarphen knew there were valid reasons for vaccine hesitancy so he wanted to personally encourage as many residents as he could to protect themselves, their families and the elderly.

“People had different thoughts. There was a lot of built-up anguish,” he says. “I needed to get out there and have the hard conversations.” Camden’s vaccination rate rose above 85 percent, and the parades set a precedent for how Carstarphen likes to get his message out.

With spring in bloom, he is back in full visibility mode, often seen with his bull-horn, working alongside residents and volunteers to literally clean up Camden. Among his Camden Strong initiatives to improve the quality of city life, the city schedules twice monthly clean-up events. In partnership with companies headquartered in the city, including Subaru and American Water, clean-up days have been well attended. Sometimes special guests show up, like U.S. Senator Cory Booker, to help spruce up cemeteries, public spaces and neighborhoods.

Carstarphen thoroughly enjoys this part of the job – talking directly to residents and being able to connect them to services they need or listen to their ideas on what his administration should tackle next. So far, the city has resurfaced 50 roads and is on track to demolish some 1,000 abandoned homes, addressing problems that have long plagued city residents.

“When I was knocking on doors campaigning as mayor, 99 percent of the people told me what they wanted to see most was us fixing roads,” he says. “Now so many people come up to me and say, ‘Mayor, thank you.’”

Building up good will is key to his more ambitious goal – getting people who left the city to return.

“I was always told by my mentors that whatever you do and however you do it, get back to your community,” he says. “Now I talk that up too. I grew up with a lot of people in their 50s now, and everybody is saying they feel comfortable coming back to visit. But I want Camden to be a place where they want to come back and call it home again.”

One of those mentors, Camden Sheriff Gilbert “Whip” Wilson says it’s been gratifying to see Carstarphen and other Camden natives – including Schools Super-intendent Katrina McCombs and Advisory School Board President Wasim Muhammad – not only taking up the mantle but bringing the dream of Camden’s return closer to reality.

“My wife Martha and I always told them to get a good education and come back home and help out,” says Wilson, a former Camden police officer who was a Camden High School assistant basketball coach when Carstarphen was on the team. “Vic is a leader. He has not dropped the ball. He’s picked it up and is carrying it on like a good point guard will do.”

A Father’s Influence

Growing up, Vic Carstarphen knew his father was known and loved in Camden for the music he made. Songs penned by his father, including “I’ll Always Love My Mama” and “Wake Up Everybody,” were the soundtrack of his childhood.

Growing up, Vic Carstarphen knew his father was known and loved in Camden for the music he made. Songs penned by his father, including “I’ll Always Love My Mama” and “Wake Up Everybody,” were the soundtrack of his childhood.

But it wasn’t until he started making a name for himself on the basketball court, playing for teams that traveled outside of Camden, that he realized his father, also named Vic Carstarphen, was famous outside of his 7-square mile hometown.

“I would be playing basketball and individuals would come up to me asking, ‘Didn’t you write that song ‘Wake Up Everybody?’” he says. “I was probably 2 or 3 years old when it came out, but they would see my name on my jersey and recognize it from the music. It always made me proud.”

Carstarphen grew up immersed in music. Legendary musicians, the likes of Leon Huff, Kenny Gamble and Teddy Pendergrass, showed up at his home for jam sessions. He was around 6 when his father did an early version of Take Your Child to Work Day, having him tag along to the studio in Philadelphia to watch the creative process unfold while recording The Jackson 5. Looking back, he says he wishes he’d paid closer attention to his father at work. At the time though, he remembers feeling fidgety. It was too much time away from the basketball court.

“My dad always wanted me to play the piano,” he says. “He would sit me down to play, and I was playing but I kept being drawn back to basketball.”

Vic Carstarphen Sr.eventually let up on trying to shape his son’s interest, instead stressing that his namesake should follow his own dreams.

“My father always told me if you’re passionate about something, it will never feel like you’re working,” he says.

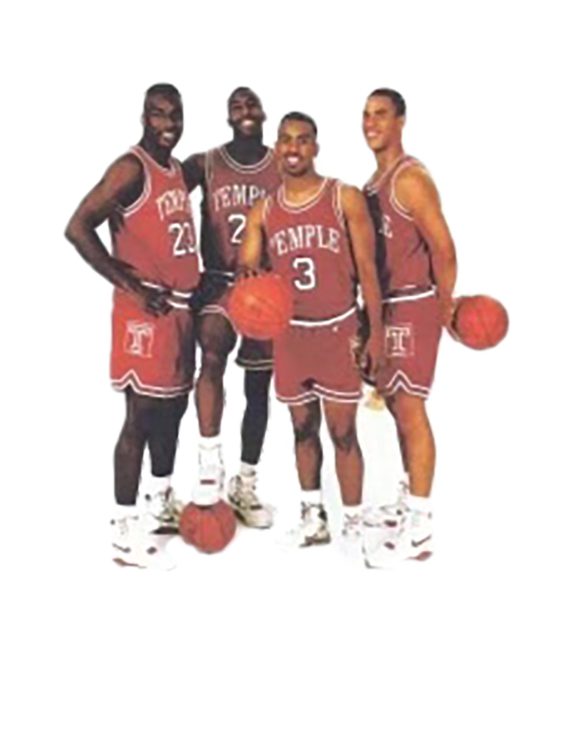

Carstarphen’s passion for basketball took him from Camden High to the Temple Owls, where the 1991 and 1993 teams made it to the Elite 8 in March Madness. He endured an injury during his senior year that derailed his dream for turning pro. And after graduating from Temple with a business degree, Carstarphen spent a few years as a sports agent, representing basketball players, before co-founding an educational testing company. He also spent some time working at a Cherry Hill-based accounting firm.

Carstarphen’s passion for basketball took him from Camden High to the Temple Owls, where the 1991 and 1993 teams made it to the Elite 8 in March Madness. He endured an injury during his senior year that derailed his dream for turning pro. And after graduating from Temple with a business degree, Carstarphen spent a few years as a sports agent, representing basketball players, before co-founding an educational testing company. He also spent some time working at a Cherry Hill-based accounting firm.

During his run for mayor and other times of challenge, he says his father’s songs often reminded him that he’s on the right path. “There was one time during the pandemic, I was driving to Town Hall for a big meeting and “Wake Up Everybody” played on the radio,” he says. “When it happens, I feel like he’s talking to me. I think ‘Dad, you’re right on time.’ He made his impact in his way, and I’m making mine my way.”