It’s very likely Phil Murphy is not even close to what you envision when you think of a government official. He wears grey running shoes with his dark button-down suits and loves a good musical. He could even sing a few show tunes for you (actually, he’d really enjoy that). He maneuvered through a kind of awkward – yet likable – ballerina leap as he walked onstage to accept his election as New Jersey’s 56th governor. And when the Eagles won the Super Bowl, he knew what to say, even though he’s a Patriots fan. “Look, when the other guys beat you, you have to take your hat off to them,” he says. “They’re the champs.”

It’s very likely Phil Murphy is not even close to what you envision when you think of a government official. He wears grey running shoes with his dark button-down suits and loves a good musical. He could even sing a few show tunes for you (actually, he’d really enjoy that). He maneuvered through a kind of awkward – yet likable – ballerina leap as he walked onstage to accept his election as New Jersey’s 56th governor. And when the Eagles won the Super Bowl, he knew what to say, even though he’s a Patriots fan. “Look, when the other guys beat you, you have to take your hat off to them,” he says. “They’re the champs.”

For the first quarter of 2018, the uber-energized new governor has hit the ground running, assembling one of the most diverse cabinets in New Jersey history, signing executive orders, hosting roundtables, and developing strategies and timelines for the state’s many challenges – challenges that many, including former Gov. Jim Florio, have described as incomprehensible.

“I quoted John Kennedy in my inaugural address: ‘We’re not doing this because it’s easy, but in fact because it’s hard,’” Murphy says.

The new governor says South Jersey residents should know he is familiar with our towns and understands our issues, and won’t forget them. We’re conducting our interview in a small conference room at Rowan College of Burlington County just after attending a student roundtable on affordable college tuition and just before attending another roundtable with Burlington County mayors.

“I’m not just saying this because it sounds good: We desperately need a governor for all 21 counties,” he says. “I love that we are having this interview in Burlington County, a place I’ve been on many, many occasions. So I’ll say to the people of South Jersey: ‘Don’t just read what I say, follow my actions.’ There are some issues that are common to every single county. But there is a whole other set of issues unique given the place you find yourself in this state.”

“I’ll give you an example: I don’t have any conversations up north about nuclear power plants. It just doesn’t come up. You come down to Salem County, you come down to the southern part of the state, and that is a do-or-die issue for the economy. It’s not just a huge percentage of our base load generation of energy, it’s a huge job spinner for thousands of people, particularly in organized labor. That’s something I care deeply and passionately about. You wouldn’t have that passion or depth or sense of it if you weren’t down here living it as we have been doing.”

“And by the way,” he adds, “you also have some outstanding wines in South Jersey.”

Murphy rattles off five of the state’s struggling cities – Newark, Trenton, Camden, Paterson, Atlantic City – and points to them as measurable indicators of the state’s status quo. “As they go, so goes the state of New Jersey,” he says.

While Murphy stresses that his administration is still researching and developing strategies, he has been quick to criticize tax incentives passed by the former administration to help business development in Camden and Newark. In February, the new governor signed an executive order authorizing a performance audit of the tax incentive programs. The audit will go back to 2010 and is expected to be completed by the end of the year.

While Murphy stresses that his administration is still researching and developing strategies, he has been quick to criticize tax incentives passed by the former administration to help business development in Camden and Newark. In February, the new governor signed an executive order authorizing a performance audit of the tax incentive programs. The audit will go back to 2010 and is expected to be completed by the end of the year.

“I’ve been very critical of tax incentives the way the Christie administration did them – that’s a one-note symphony, and it’s only for big companies,” he says. “Tax incentives…have to be the icing on the cake, not the cake itself. It’s hard to swallow when you see $8 billion in corporate tax breaks on one hand and $8 billion in cuts to public education on the other. And it’s even harder to swallow when, at the same time we were handing out these billions in tax breaks, our economy continued to lag behind nearly everyone else in the nation. The people of New Jersey deserve to know what, exactly, they got for their $8 billion.”

“But I do think there is a place for tax incentives,” Murphy continues. “Camden is on the list of a handful of communities where it can be beneficial to take advantage of creative initiatives, whether it’s an urban enterprise zone or opportunity zones, which are a concept in the nation’s new tax bill, thanks to Sen. Booker. I would hope that we could use weapons like that to continue to invest and attract investment in the Camdens of the world.”

As for Camden’s transforming education system, Murphy has met with Superintendent of Schools Paymon Rouhanifard, who was appointed in 2013 as part of the state takeover of the city. Rouhanifard is under contract until 2019, and has expressed his commitment to his job and the students of Camden. “I sat with Paymon,” Murphy says, “and I am impressed by him. I respect him.”

Murphy has been decisive on two issues which he included in his campaign: boosting the state’s medical marijuana program and legalizing recreational marijuana. The first step, he says, is to increase accessibility to medical marijuana. As one of his first acts, the governor signed an executive order giving the Dept. of Health and Board of Medical Examiners 60 days to review the current law, which was enacted in 2010. The state law limits medical marijuana to certain conditions and contains regulations that have restricted the number of new dispensaries.

“There are 9 million people who live in the state. About 15,000 are enrolled in the program,” Murphy says, “but there are only five dispensaries. Michigan is about the same size of our population, and they have 220,000 to 230,000 patients enrolled.”

“The more we studied the medical marijuana reality in the state, we realized this actually was a life-or-death or, at minimal, a quality of life issue,” he says.

Murphy also believes it’s time for the legalization of recreational marijuana, but says there is no time frame for that change. “We have not put the wheels in motion,” he adds. “But it’s something we’re committed to.”

He says his motivation for legalizing marijuana is not solely the economic benefit to the state, although that plays a role, but it’s more about correcting a racist criminal justice system.

“If my reasons to do this were a long train with many cars, the economic incentive would be the caboose. The engine is social justice,” Murphy explains.

“We have the widest white/non-white gap of persons incarcerated of any state in America. If you’re a young, particularly black male vs. a young, non-black male, the chances of getting hauled in and doing time for a low-end drug crime are dramatically different. The main reason to do this is to break the back of the social justice inequity.”

Many of Murphy’s plans bring a new way of thinking to the current way of doing things. The biggest sign of that? His cabinet. Murphy’s Lt. Governor Sheila Oliver is a Black woman, and Gurbir Grewal is the first Sikh to serve as attorney general in the country. And for the first time in New Jersey’s 242 years, the majority of a governor’s cabinet appointments are female.

“I’m a former national board member of the NAACP, so it’s through that lens I see the world,” Murphy says. “The team we’ve nominated is extraordinarily diverse, and that isn’t by accident. Our obsessions were competence and professional capabilities – that’s a must, that’s a given. But then, diversity.”

Murphy has a list of issues he sees his team addressing – the environment, funding public higher education, infrastructure – but he believes it all comes down to helping state residents, especially the middle class.

“I want our team,” Murphy adds, “to be the one that says to the middle class and those who aspire to be in the middle class: ‘You know what, we’ve got your back. Help is on the way.’”

First Sign: Gender Equality

First Sign: Gender Equality

Gov. Phil Murphy’s first official act after being sworn in to office was to sign an executive order in support of equal pay and gender equality. In New Jersey, women working full time earn, on average, 82 cents for every dollar earned by a man in a full time position. For black women, that lowers to 58 cents and for Latina women, 43 cents. The executive order prohibits state agencies from asking a job applicant for their past wage history.

“Other states have done it, so we’re not George Washington here,” says Murphy. “It’s predicated on research that says women – particularly women of color – started out in a hole, way back when they started their professional career, and then every step subsequent to that as they changed jobs, when asked what their salary was, it was lower than the expectation. And I assume a lot of this is human nature as opposed to willful misconduct – although I’m sure there is a bit of both – but the employer thinks, ‘Hey wait a minute, I thought she was going to say she was getting $35,000, she’s only getting $30,000. I thought I would have to offer $40,000, but I can get away with $35,000.’ Those days are over in our government. I say it’s a first step, because I’d like this to be the law of our land, requiring not just state government and agencies to prohibit that salary inquiry, but to make this a law for every player in the state.”

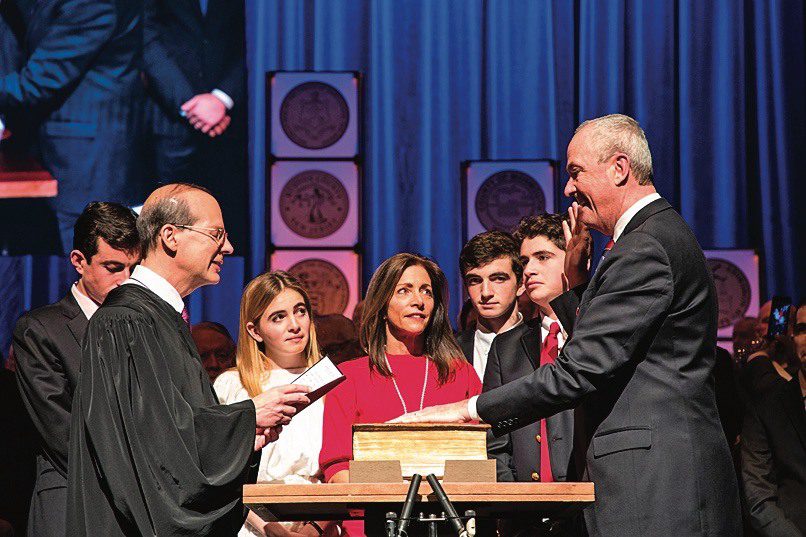

What’s so special about that Bible

At his inauguration, Gov. Phil Murphy was sworn in with his hand placed on the leather-bound Bible used by John F. Kennedy during his 1961 presidential inauguration. The Kennedy bible was a family heirloom, having been brought to the United States from Ireland, and is housed at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston. It contains the family’s handwritten notes dating back to the 1800s. A native of Boston, Murphy has often cited Robert and John F. Kennedy as his personal heroes.

At his inauguration, Gov. Phil Murphy was sworn in with his hand placed on the leather-bound Bible used by John F. Kennedy during his 1961 presidential inauguration. The Kennedy bible was a family heirloom, having been brought to the United States from Ireland, and is housed at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston. It contains the family’s handwritten notes dating back to the 1800s. A native of Boston, Murphy has often cited Robert and John F. Kennedy as his personal heroes.