In 2010, Susan Mitchell* was a veteran middle school teacher who loved her job and her students. When she first began having trouble catching her breath, the now 58-year-old didn’t think much of it. But her symptoms worsened, and she was ultimately hospitalized for 10 days as doctors treated Lyme disease that had gone unchecked long enough to affect her heart.

Mitchell, a Mount Laurel resident, recovered from the close call that summer, but when school began again in the fall, it was clear her ordeal was far from over.

“When I went back to school, I was moving from fifth to second grade, so I had a lot to learn,” she says. “I felt very stressed and emotional, but I thought it was just having to learn all the new content. Those feelings didn’t go away, and as that school year passed and then the next, I knew I wasn’t myself. I was experiencing a lot of fear; I just didn’t feel confident. I knew something was amiss, but I couldn’t put my finger on what.”

Mitchell began to have lapses in memory. The slips were almost unnoticeable at first, but gradually worsened, causing her to question everything: her ability to teach, her self-image and even her own brain.

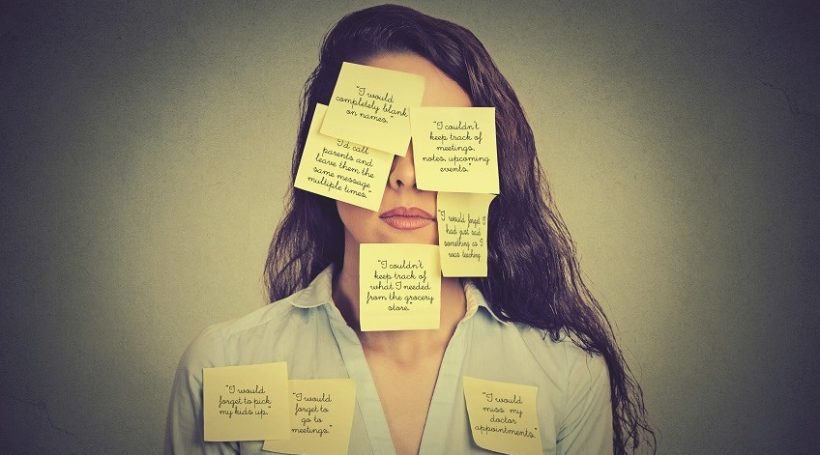

“I couldn’t keep track of meetings, notes, upcoming events. I wound up carrying all my papers around with me, because I was afraid if I filed them I’d never find them again,” she says.

“I would completely blank on names. I’d call parents and leave them the same message multiple times. I would forget I had just said something as I was teaching, and the kids would say, ‘You just said that!’ By the end of the day I was practically in tears. I was scared. I knew in May of 2014 that something was seriously wrong.”

Fearing the worst – early-onset Alzheimer’s, she says, or a brain tumor – Mitchell sought out a neurologist, who failed to find anything structurally wrong with her brain. But cognitive testing showed something was wrong with her brain – just not problems that would show up on any MRI.

As a result of her bout with Lyme disease, Mitchell was suffering from executive dysfunction, a disruption of the cognitive processes controlled by the frontal lobe of the brain. These include concentration, memory and decision making, says Karen Lindgren, MD, senior neuropsychologist at Bancroft NeuroRehab.

“In general, executive function refers to the cognitive processes that help us navigate through life,” Lindgren says.

“These are skills that help us problem solve, plan, mentally organize things and control our behavior. All the things you think about during the day that you don’t act on or say out loud – that’s your executive function helping you make controlled decisions. It’s what helps you decide and remember what you need from the grocery store and how much time you need to cook dinner.”

Executive dysfunction – the interruption of some or all of those cognitive processes – can appear after a traumatic brain injury or, as in Mitchell’s case, after an illness. It’s also common, Lindgren says, to see executive dysfunction develop as people age.

“The changes may be very subtle at first,” Lindgren says. “The mom who has been planning Christmas dinner for 50 years is suddenly making mistakes, not leaving enough time to cook. Maybe a parent tells an off-color joke or is running late when they used to always be on time. Often family members question, ‘Is this really a change? Were they just having a bad day?’ People might think, ‘Well, they’re retired, they’re not so tied to the clock.’ When you start to see things that are concerning – a parent feels overwhelmed or is saying things they might never have said before – that’s when you really want to start thinking about getting an assessment.”

The assessment consists of a series of six-hour standardized tests that focus on attention, memory, problem solving, language and emotional function. The results allow doctors to analyze which parts of the brain are working normally and whether the patient is showing signs of executive dysfunction.

Similar tests are used to identify executive dysfunction in children and adolescents. In those cases, the problem is often not the result of an injury or illness, but a developmental issue that presents itself as a child’s brain develops, says Mala Gupta, MD, of Centra Comprehensive Psychotherapy and Psychiatric Associates.

“Sometimes it presents as a behavioral problem, sometimes as an academic problem or even a social problem,” says Gupta, director of child and adolescent psychiatry at Centra. “Parents will come in at the end of their rope because their child absolutely cannot focus or can’t handle time management or has no impulse control, or the child has suddenly become someone the parents don’t recognize. People will come in and honestly speak almost as if they dislike their own child, because the family is so strained and nobody can figure out a solution.”

Gupta says children who are suffering from executive dysfunction often have issues in an area called working memory.

“It’s the ability to hold information you recently got in your short-term memory, access other information and then complete a task or make a decision,” she says.

“So let’s say you gave me a phone number, and I wasn’t able to write it down right away, so I held it in my mind until I had a pen and paper. Or I looked something up and held the number in my mind until I dialed the phone. That’s working memory, and problems there are absolutely one of the biggest things we see with executive dysfunction.”

Gupta says that while working memory may seem like a small aspect of brain function, a dysfunction can affect countless aspects of a child’s life, resulting in extreme frustration and behavioral issues.

“Parents come in and say, ‘My 11-year-old cannot get ready in the morning. I tell them all they have to do is go upstairs, get dressed and brush their teeth. Why can’t they do it?’ They can perform those individual tasks. The problem is if they don’t have good working memory, they’re not going to be able to complete them. That may mean getting distracted or starting to think about something else. So instead of being able to plan appropriately and accomplish simple tasks, they come to a complete stop.”

Gupta says executive dysfunction can drastically affect a child’s academic performance. Math and reading require high-functioning working memory, comprehension and mental organizational skills. It can be extremely frustrating for a child, she says, particularly because an executive dysfunction has no impact on – and does not indicate – intelligence.

“Most kids are not lazy or trying to be mean or trying to be oppositional. They’re struggling with something,” she says. “It is a horrible feeling for a child to sit in a classroom and think, ‘I am just as smart as my friends – why am I not getting better grades? I’m an idiot. I’m a loser.’ It has a terrible emotional impact on them and on their families.”

Gupta says she works to accentuate the strengths of her patients’ cognitive abilities, which is encouraging for both her young patients and their parents.

“I say to the parents, ‘Look you guys, this is not about your child’s character, her personality or your relationship,’” Gupta says. “It’s a great relief for a patient when you explain that what they are going through is separate from their personality. You say, ‘This is not a part of your personhood, and we are going to help you figure this out.’”

When she met with her doctor after her cognitive testing was complete, Mitchell says she was relieved to finally understand what was happening inside her head.

“She said my brain was damaged, and it couldn’t field multiple pieces of information at once,” Mitchell says. “My brain was overloaded, so my attempts to utilize memory strategies were inefficient and frustrating. I just thought, ‘Finally!’ It was such a relief to know what was going on, and then on top of that, I was treated for the depression and anxiety I’d developed due to the loss of my abilities.”

Once the problem is diagnosed, Lindgren says, the journey to wellness is just beginning. Often patients undergo months – and sometimes years – of therapy to regain or replace the abilities they’ve lost.

“There is a branch of treatments called cognitive rehabilitation,” she says. “Sometimes it’s about recovery, and sometimes it’s about compensation. So a simple compensation strategy would be: Instead of knowing in your head that dinner needs to be ready at 6, so you need this much time to grocery shop and this much time to cook, you use a calendar and alarm.”

Mitchell says doctors and therapists worked with her to create compensation strategies and workarounds, including memory processes to help her stay organized and frequent “brain breaks” throughout the day. Though she’s still navigating the emotional minefield of her executive dysfunction, Mitchell has come to terms with the way her brain works now.

“I’ve had to forgive myself and be kind to myself,” she says. “I used to be very good at navigating and finding back roads. Now I get lost, even with my GPS. That’s maddening, and it makes me feel so stupid. So I pull over and cry, and then I pull myself together and say, ‘OK, you can find your way.’ I have to give myself the leeway I’d give anyone else.”

As a result of her symptoms, Mitchell was forced to give up her full-time teaching job, and though it was difficult, she says it’s freed up time she now devotes to a cause she finds deeply meaningful.

“I’m a firm believer that when doors close, others open,” she says. “I went to Rutgers and majored in African-American studies. I’ve always had a heart for kids in Camden and always felt like I needed to be doing something more for the children of that city. Now, I’ve partnered with a nonprofit where I help kids with their homework and do one-on-one sessions to help kids with their reading.”

“I mourned the loss of an ability and the loss of a career,” she adds. “I lost some things. But I’m dwelling on what I gained. When you work with these kids and they see you care about them, their hearts open. I’m thankful for what’s in my life now and for the things I still do have.”

*Name has been changed