The artist, Drew Cameron, began traveling around the country hosting papermaking workshops for other veterans. His unique idea sparked the nonprofit Combat Paper New Jersey, which now teaches veterans how to use papermaking to express their thoughts, memories and lasting impressions of the war.

“It started as a protest, but it grew into something bigger,” says Dave Keefe, an artist and co-founder of Combat Paper. “Veterans were tapping into the process of storytelling through art and papermaking. After [Cameron] brought it to the Printmaking Center of New Jersey, everyone quickly realized it should be a permanent program in New Jersey.” Papermaking for veterans is now a weekly class at the center, and workshops are held along the East Coast.

When Keefe got involved in 2011, he’d been out of the Marines for about three years. He joined the reserves in 2001 and was deployed to Iraq from 2006 to 2007.

“When I was first asked to lead the program, I said no,” Keefe says. “I felt like it was not my thing. I was a painter with an MFA in studio art, and I was teaching painting at Montclair State University. I wasn’t ready to cut up my uniforms even though I was painting – or trying to paint – about my military experiences.”

“But I was in a bad place in my life, and I needed a change,” Keefe continues. “It turned out I needed this community of veterans who were artists. I called back and said, ‘OK, let’s see what happens.’”

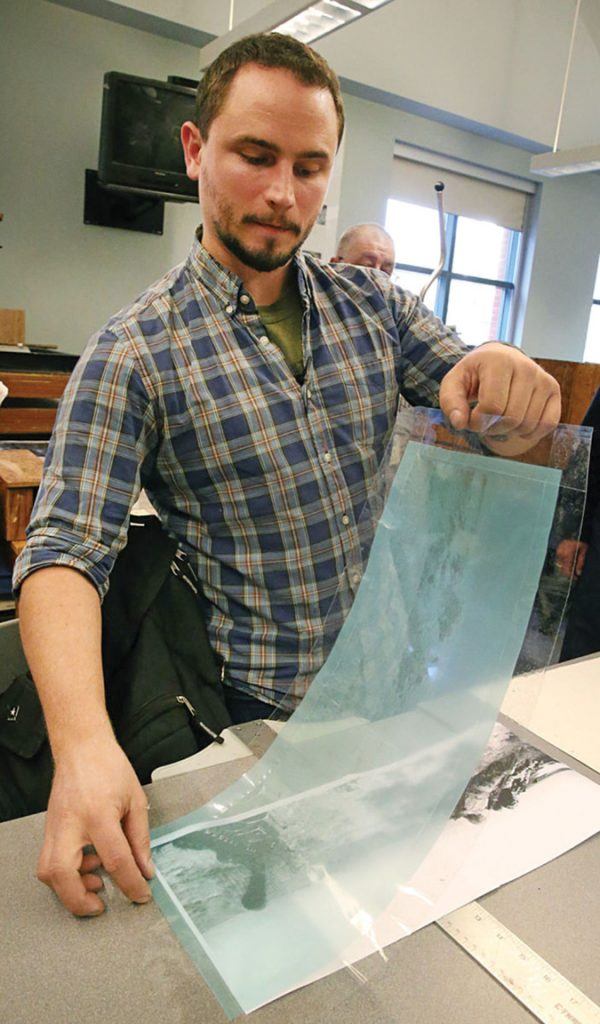

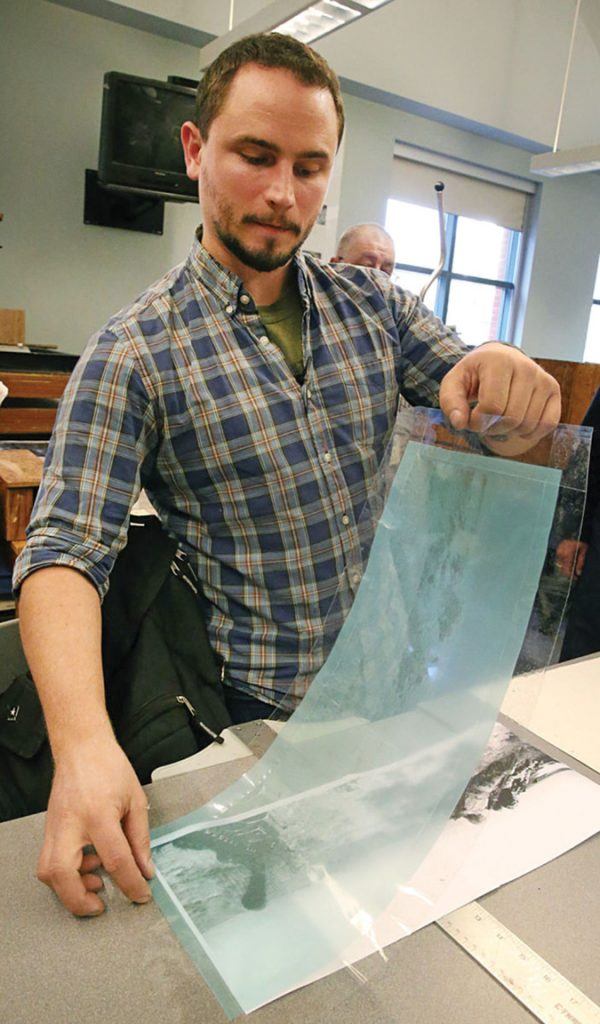

The first time he participated – cutting apart a uniform, cooking the pieces down in a pulp-churning machine called a Hollander beater, forming the pulp in a mold and pressing it into paper – Keefe says he felt an intricate mix of emotions.

“It was intense,” he says. “We explain it as a deconstructing; you’re literally pulling apart the fibers of the uniform and at the same time pulling apart the experiences associated with it. You’re transforming that experience, reclaiming it and repurposing it in a new way.”

Whether the experiences a veteran associates with the uniform are good or bad, Keefe says many find the process of dismantling them cathartic.

“It’s heavy,” he says. “You’re talking about very personal experiences that are traumatic or terrible, or sometimes really good experiences that you just miss – the camaraderie, the purpose. Here’s this uniform you wore for years, ironed forever, and you’re taking it apart.”

“It’s jarring. It’s a paradigm shift. You’re changing your past by reclaiming it in the present. It’s hard to comprehend that happening in one sitting at a table with scissors, but you do it anyway, because you’re around people who can understand you and are willing to listen.”

Keefe developed a five-day workshop to teach veterans the basics of papermaking. Once they master those skills, Keefe and the other instructors encourage the veterans to use the paper to create something new, like a painting, poetry piece or screen print.

The group approached universities to ask about hosting workshops for student veterans. “We set up our first workshop in 2012 at Montclair State, and it just blew up from there,” Keefe says. “Everybody wanted us. Universities across New Jersey were contacting us.”

Soon, the group was hosting workshops at Rutgers, Princeton and Stockton Universities. The organization received large grants from Impact 100 Garden State and the Wounded Warrior Project.

Over the past few months, Combat Paper NJ has built a relationship with Grounds For Sculpture in Hamilton, hosting workshops in the spring and summer that culminated in an extended exhibition. That program will be held again in 2017.

Last year, Combat Paper NJ outgrew the Printmaking Center, and Keefe formed a larger, parent nonprofit – Frontline Arts – to bring together community and social justice organizations centered around creating art that tells a story.

Keefe says the programs Frontline Arts sponsors, which often include poetry readings and art exhibitions, aren’t just about the veteran artists. Just as vital, he says, are the non-veterans and the community at large who show up to hear the stories told.

“Vets in this day and age have this real desire to express their stories,” Keefe says.

“Combat Paper and our other groups focus on veterans who don’t have a voice, who need a platform of support to tell their stories. They feel disenfranchised, marginalized and ostracized. That’s where we focus, because that’s where we feel like the real stories are. It’s not solely about veterans, but about building a community. The most profound moment is when you have these vets getting up in front of people and reading their poetry or displaying their work. The physical presence of their vulnerability is shocking. The non-veterans being able to relate to them and vice versa; that connection is the golden moment for me.”

For some veterans, the chance to take something full of often-traumatic memories, transform it into what Keefe calls a “blank slate” and use it as the base for an artistic expression is both symbolic and therapeutic.

“Some of the people we work with are Vietnam vets who have these terrible, terrible stories – stories they haven’t told in 50 years,” Keefe says. “They’ll come up to us frequently and say, ‘You saved my life,’ and we say, ‘No, we didn’t. You did.’”

While he acknowledges the risks veterans face and knows Combat Paper has been a lifeline for some, Keefe isn’t out to fix anyone. Though the nonprofit does frequently work with art therapists, he rejects the idea that the program’s goal is to help veterans “get better.”

“Therapy is an easy way for the public to understand things, because it makes them feel better,” he explains. “That can almost be detrimental to the community. For us, it’s not about ‘healing.’ It’s about opening up the wounds so we can talk about them. Organizations talk about healing because it completes the arc: You go off to war, you come back, you’re screwed up and then you get better. That narrative needs to be broken down.”

Keefe hopes to increase the visibility among the greater public of programs like Combat Paper NJ and the other partners of Frontline Arts, with the ultimate objective being more understanding and maybe even fewer wars.

“We want to challenge the way people think of veterans or the way we go to war or what happens in war,” Keefe says. “These programs aren’t healing the veteran so much as healing society. The experiences – and the public telling of them – is what’s going to create some kind of change.”