State officials recently named heroin addiction as the No. 1 health crisis affecting our young people – and those young people live all over New Jersey, not just in poor, crime-ridden towns. Some may even live on your street, attend the same school as your child or be the son or daughter of your close friend. The growing epidemic has sparked Camden County to introduce new ways to get help to addicts. With the help of parents who have experienced their greatest loss, government and law enforcement officials are stepping in to combat the deadly problem. You may want to learn as much as you can about their efforts, maybe even volunteer to help, because the problem they’re fighting is right in your backyard.

Since the day her son Sal died from a heroin overdose, Blackwood resident Patty DiRenzo has thought obsessively about what could have been done differently to save his life. What if the treatment he so desperately needed was available when he had reached out for help? What if someone had called 911 after Sal’s final overdose, when he was slowly dying on the streets of Camden?

Sal is typical of many young adults who never imagine their casual use of drugs can lead to a deadly habit. Sal was trying desperately to beat the addiction, DiRenzo says, and his death at age 26 was accidental and preventable.

“It didn’t sit right with me,” she says. “We’re losing kids every day to overdoses. Something had to be done to keep these kids alive until they could find proper treatment.”

In the five years since her son’s death, DiRenzo has been working to help others escape the same tragic fate. Her latest triumph – Operation SAL – helps those struggling with addiction to break free of their dependency. As a result of Operation SAL, officials from Camden County government, hospitals and law enforcement have agreed to provide – and pay for – immediate detoxification and treatment services to overdose survivors.

Under the new program, overdose survivors willing to enter treatment will be released to Delaware Valley Medical in Pennsauken for detoxification and intensive outpatient services – all paid for by the county. From there, they may be moved to inpatient therapy or continue with outpatient help, depending on their need. In the pilot year, the county is providing $150,000 to pay for the treatment. All four hospital systems in the county – Kennedy, Virtua, Cooper and Our Lady of Lourdes Medical Center – have pledged to retain the patients until the transfer to Delaware Valley is arranged. No one will be released back to the streets if they are willing to accept treatment.

Operation SAL is one of several efforts in Camden County aimed at combating the increasing problem of heroin overdoses. Last year, the state declared heroin addiction “the No. 1 healthcare crisis” affecting countless young people once thought to be at low risk of addiction. The vast majority of addicts come to their dependency through prescription pain pills, sometimes legitimately acquired but also easily obtained on the streets, according to a 2014 report by the Task Force on Heroin and Other Opiate Use by New Jersey’s Youth and Young Adults.

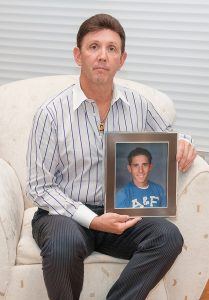

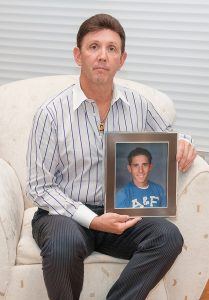

Increased awareness of the heroin epidemic has discredited conventional wisdom that drug addiction was not a problem for college-bound kids from “good” families, says Gregg Wolfe. The Voorhees father started the advocacy group Squash The Secret after his 21-year-old son Justin died of a heroin overdose in 2013.

“More and more, the truth is starting to come out,” says Wolfe, who has testified before Congress in favor of laws to direct more resources toward treating addiction. “People are starting to understand this is a disease, as opposed to users being the scum of the earth.”

DiRenzo and Wolfe are among a growing number of South Jersey residents who – fueled by grief and anger over losing loved ones to overdoses – are helping to reform drug policy, ushering in new laws and even changing the way people view addiction. Through DiRenzo’s advocacy, the state’s seminal Overdose Prevention Act was passed in 2013. Among key reforms, the law protects people from prosecution for calling 911 to report an overdose. On the day Gov. Chris Christie signed it into law, DiRenzo was by his side.

“He said my constant letters pushed him to sign it,” she says. “I just didn’t give up.”

Other victories have snowballed from the law, including the widespread use by police and other first-responders of Naxolone (also known by its brand name, Narcan), which acts as an antidote to opioid over-doses. Hundreds of overdoses that could have resulted in deaths were avoided with the use of Naxolone. Among Camden County police officers alone, 155 overdose reversals have been logged in the city since they began using the anti-opioid medication in May 2014.

Following the lead of the state, Camden County formed its own Addictions Awareness Task Force last year. A key component of its mission has been education and building awareness, says Camden County Freeholder Director Louis Cappelli. Among its most successful campaigns, billboards strategically located in high-trafficked areas have helped to change the conversation about drug abuse, he says. The billboards, featuring clean-cut white teenagers and hotline information, herald the task force motto: “Heroin. Pills. It All Kills.” An additional message is included: “It’s not miles away. It’s not other kids. It’s right in your backyard.”

Marla Meyers, JFCS executive director, says the agency is ready and eager to bring the program to any and all groups – religious or secular – that want to get the message out.

“Through the program, we’ve instilled in kids the understanding that you can’t try this stuff even once, because you don’t know how your body will react to it,” says Meyers.

The county’s latest effort, Operation SAL, is viewed as the logical progression in efforts to help people who were revived by Naxalone.

“Operation SAL is the next step for us in attempting to find ways to help those with addiction problems,” explains Cappelli. “We’re hoping we will have some luck getting people to begin treatment.”

How many it will help is hard to say, Cappelli adds. Operation SAL is a start, but it does not remove the obstacles addicts face obtaining long-term help. Most insurance companies won’t pay for treatment, and there is a shortage of beds available both in New Jersey and across the nation in long-term treatment centers.

“If it’s successful and we have more demand, we will find ways to raise the money to help people, but there is only so much we can do,” notes Cappelli. “There really needs to be a national dialogue and commitment to addressing this issue.”

For DiRenzo, it’s both an honor and fitting that an initiative to help those trying to become drug free is named for Sal, the younger of her two boys who was “an amazing son, brother and father who unfortunately also struggled with addiction.”

Like so many of heroin’s victims, nothing about Sal’s upbringing would have indicated he would become an addict. He loved sports and was a good kid, she recalls. The first indications of drug trouble came in middle school with marijuana experimentation.

“I never blame anyone, but I think peer pressure had a lot to do with it,” says DiRenzo. “He just wanted to be one of the crowd, and he never felt like he could say no.”

Pot led to pills in high school and, by his early 20s, a full-blown heroin addiction.

Around 2008, Sal was in remission, being treated with Suboxone, a legally prescribed opiate that virtually stops withdrawal symptoms. During those good years, he put himself through Pennco Tech, graduating at the top of his class in commercial heating and air conditioning. He had a job and a girlfriend, and was well on his way to rebuilding his life when he decided to take it upon himself to wean off the Suboxone. This decision coincided with the news of his mother’s diagnosis of stage IV breast cancer and his girlfriend’s pregnancy in the spring of 2010.

“We didn’t realize at the time these would be triggers that would set him back,” DiRenzo says. “It happened so quickly, we couldn’t catch it.”

To deal with withdrawal from Suboxone, Sal started using pills, which very quickly led him back to heroin. Like other times in the past, the family’s efforts to get him the help he needed fell short. After losing his job, DiRenzo explains, Sal could no longer afford insurance. But, she adds, even with insurance, Sal may not have been eligible for a more intensive treatment program.

Released involuntarily from an intensive in-house treatment program for lack of funding, Sal was in an outpatient program and seemed to be returning to his healthy self when Camden police found him in DiRenzo’s car on September 23, 2010. He had been robbed and was unresponsive.

DiRenzo believes that if the 911 law been around at the time, the person who was with Sal when he overdosed might have called for help. Had Operation SAL been established, Sal may have ended up in recovery.

Knowing that such measures are now in place is bittersweet, DiRenzo says. Although Sal never got the opportunity, other people will surely benefit, which is why she feels it’s so important to continue talking publicly about her son, particularly to police officers and other first responders who are in a position to reverse overdoses.

“It’s hard to constantly be reliving his story, but I know I’m doing this to help other people,” she says. “No one should be afraid to call 911 to help someone. No one should be left alone to die.”